Sapience's "The Death of Neo-Darwinism": A review

The book's stated goal, its *actual* goal, and how to do better

The Sapience Institute, a renowned Islamic da’wa and apologetics think-tank, has come out with a new publication entitled The Death of Neo-Darwinism: Dawkins vs. Noble, written by Subboor Ahmed and Salman Butt. As the title suggests, the book offers a critique of “Neo-Darwinism” as exemplified by the thoughts of Richard Dawkins, using the arguments made by the British physiologist Denis Noble.

What follows are my thoughts on the overarching argument developed of the book. I found this to be a challenging read, mostly because I was confused about what the premise of the book was supposed to be and its relevance to Islam-evolution apologetics. It’s only after I read through several chapters that I realized what the actual goal of the book was - a critique of certain forms of biological reductionism. To my mind, I think this confusion was caused by the author’s choice to center the book around “Neo-Darwinism” and the particular way Noble, and the authors following him, define it.

In the first part of this brief review, I explain why the stated goal of refuting Neo-Darwinism as defined in the book made little sense to me. I then attempt to reconstruct what the actual aim of the book is, and whether Noble’s arguments have much utility to achieve that end. I conclude with reflections on where this work fits in the broader context of Islam-evolution apologetics. Note that this won’t be a beat-by-beat analysis of every argument made in the book, just the overarching project it pursues.

Refuting Neo-Darwinism is akin to beating a very dead horse

The authors, quoting Noble, ascribe these four pillars to Neo-Darwinism:

(i) [T]he hypothesis that alterations in the structure and function of organisms within a single generation cannot be transmitted through the germ line (henceforth, Weismann barrier pillar);

(ii) the hypothesis that organisms are incapable of changing their own genetic makeup, making causation unilateral and not allowing for the possibility of the environment to affect genes (henceforth, central dogma);

(iii) the hypothesis that an organism is a passive vessel for preserving genes within a pool, and that the behaviour and function of the organism work toward this purpose (henceforth, passive filter pillar);

(iv) the hypothesis that evolution occurs through minor random alterations in genes that are passively favoured through a process of natural selection (random error pillar). [pp. 12-13]

If the premise of the book - debunking Neo-Darwinism - is to have any contemporary relevance, the view has to have widespread agreement among evolutionary biologists working today. And yet, defined as above, Neo-Darwinism is not only dead and irrelevant in today’s academia, but it’s been dead for decades - and all evolutionary biologists would accept this.

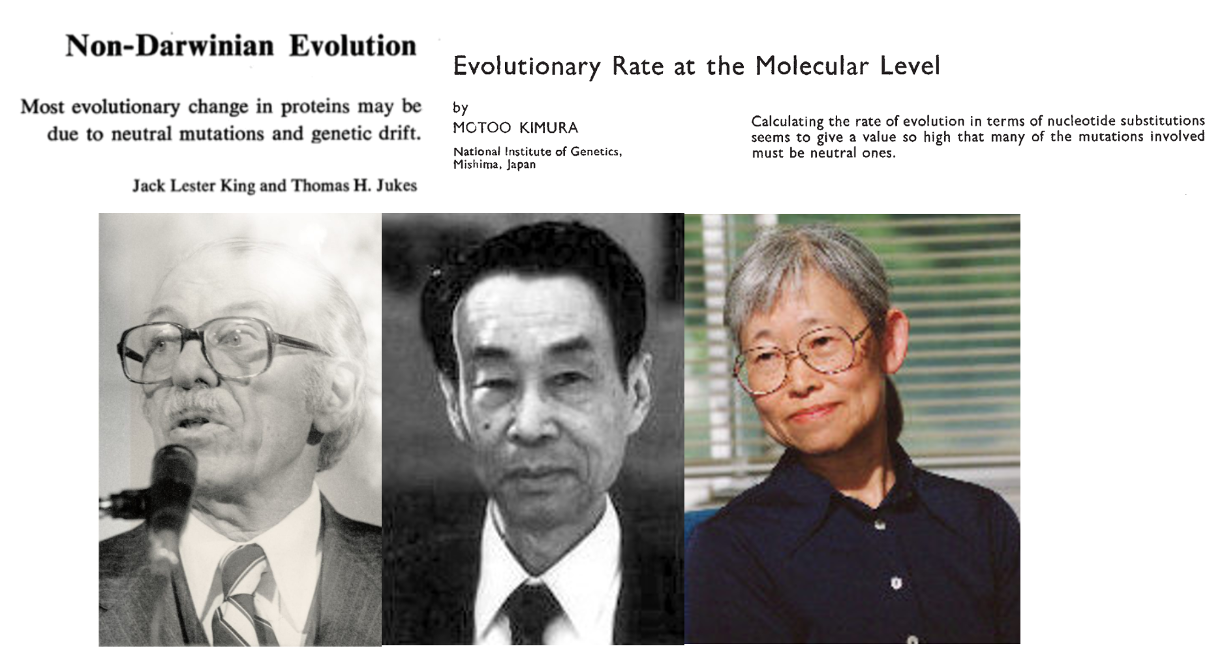

This can be seen most explicitly if we look at the fourth pillar which defines the sole engine of evolutionary change: natural selection acting on “minor random alternations”. Way back in 1968, Kimura published evidence to the effect that most genetic variation is "neutral" - i.e., neither beneficial nor detrimental, and therefore effectively invisible to natural selection - in his highly cited Nature paper Evolutionary Rate at the Molecular Level. Next year, King and Jukes published Non-Darwinian Evolution in the journal Science, with the tagline most evolutionary change in proteins may be due to neutral mutations and genetic drift. These two papers introduced and cemented genetic drift as one of the key engines of evolution, subsequently refined by the work of Kimura's student, Tomoko Ohta.

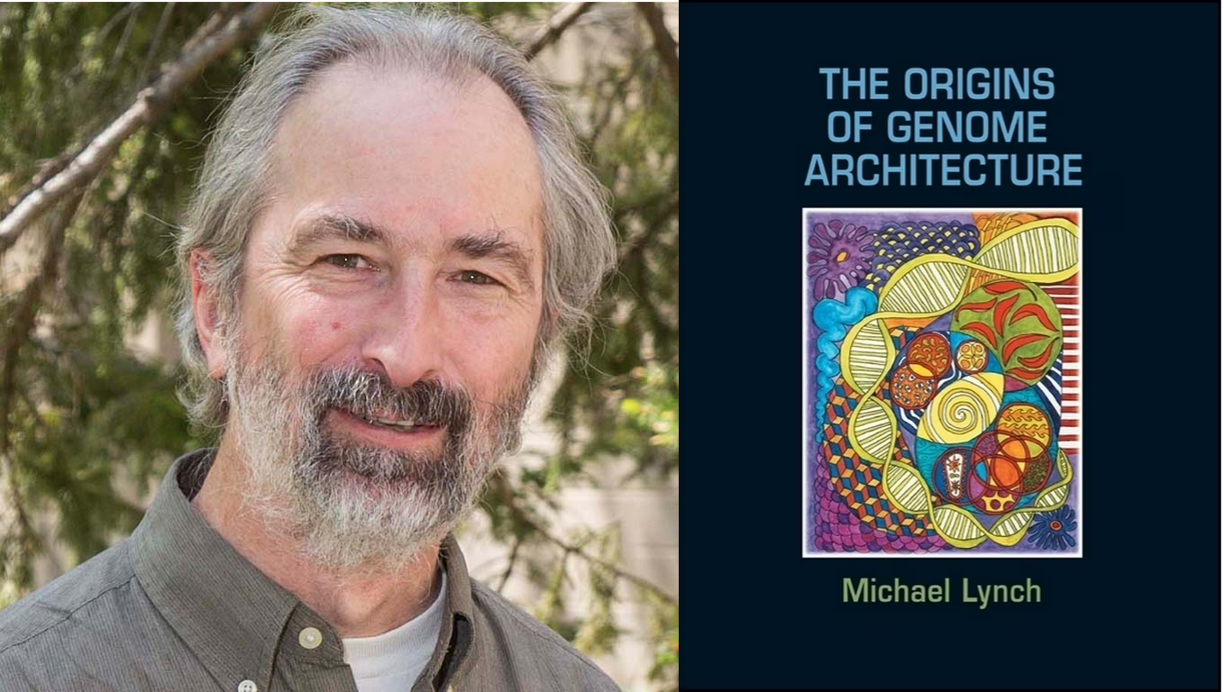

Around the same time, scientists started to appreciate the outsize role mutations have in generating variations - not just boring, small-effect point mutations (“minor alterations” as stated in the fourth pillar), but large-scale genome rearrangements. This undercurrent was synthesized in Susumu Ohno's influential book Evolution by Gene Duplication; but the role of gene duplications in generating evolutionary novelty has been appreciated for nearly a century - read Dietard Tautz’s Discovery of De Novo Gene Evolution for a readable, if not opinionated, review on the history of this line of thought.

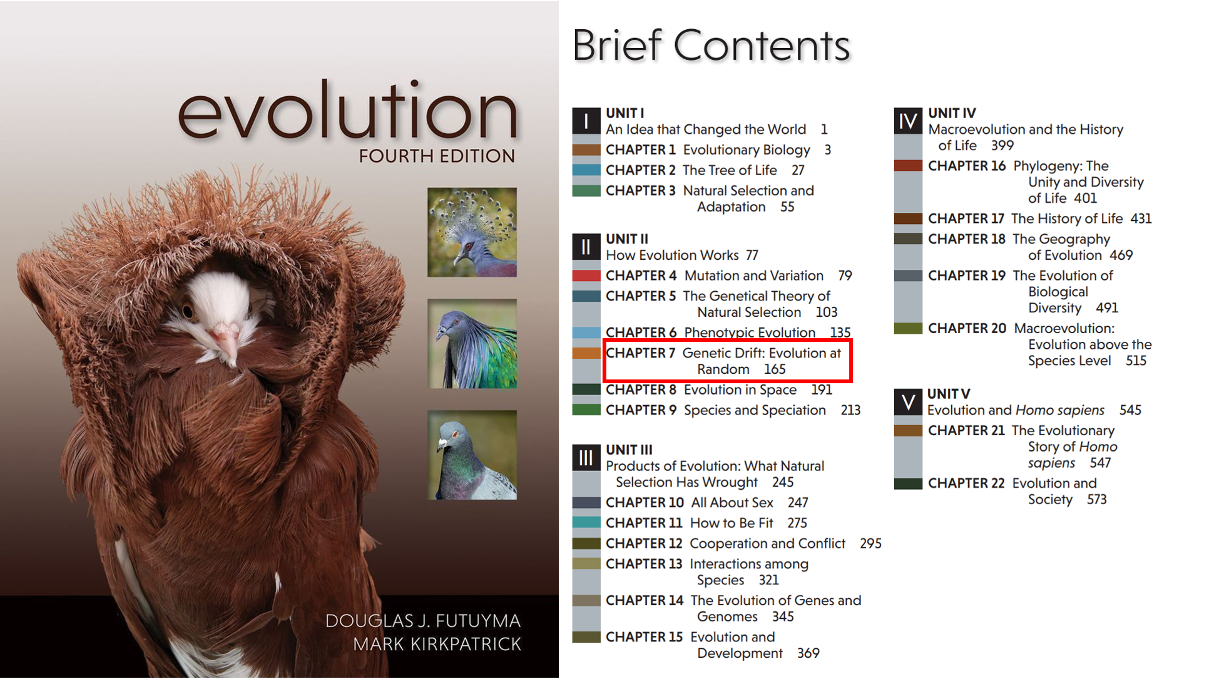

These two ideas - genetic drift and large-scale genome rearrangements as among the major drivers of evolutionary change - have been the mainstay of evolutionary orthodoxy for the past few decades. Every evolutionary biology textbook of note has chapters dedicated to these concepts, every undergraduate-level evolution class teaches them; and every evolutionary biology researcher worth his salt, in attempting to explain natural phenomena, would consider drift or mutation biases as potential explanations. No evolutionary biologist in their right mind would accept natural selection as the only explanation driving evolutionary change.

This is why attempts to refute Neo-Darwinism need a stronger metaphor than just "beating a dead horse". Not only has the horse been well and truly dead for a long time, its corpse has disintegrated into dust. Really, if you want evidence against Neo-Darwinism - all you need to do is pick up an evolutionary biology textbook and read the chapter on drift.

And yet, from reading the book, one gets the impression as if the authors believe Neo-Darwinism is still thriving in contemporary evolutionary biology academia. Here’s an excerpt from the introduction:

These claims are surprising for large swathes of the scientific community to whom Neo-Darwinism remains as indispensable a theory today as it was when it was first formulated. Neo-Darwinism—defined loosely as Darwinism coupled with Mendelian genetics—forms the cornerstone of modern evolutionary theory. This centrality of Neo-Darwinism has led to it being the subject of countless peer-reviewed articles, classroom exercises, and seminars in lecture halls over the past century. [p. 5]

Likewise in one of the concluding chapters of the book:

Beginning with biochemistry—and having been proselytised like the rest of my cohort into the central dogma of Neo-Darwinism—I was once a believer of the school of thought I now write against. [p. 83]

Unless this brother went to school at least thirty years ago - both of these quotes are completely at odds with how evolutionary biology is taught in textbooks and classrooms, or how research in this field is conducted.

Why not use stronger, more widely accepted arguments to refute Neo-Darwinism?

Despite all of this, say we’re still on board with the book’s stated project. How would one go about refuting Neo-Darwinism?

As mentioned above, the easiest, most accessible way of understanding why Neo-Darwinism is wrong is to read an evolutionary biology textbook written some time in the past couple of decades. You could read the chapters on genetic drift, gene duplication, symbiogenesis, mobile genetic elements - any chapter adjacent to these avenues would quickly disabuse you of the fourth pillar of Neo-Darwinism.

However, despite the plentiful abundance of these tools, the authors instead choose to use arguments made by a British physiologist who, as I understand, doesn’t have any direct expertise in evolutionary biology. Some of his ideas are controversial, but even if they weren’t - there are much more potent and widely agreed-upon options to use if the goal was to just disprove Neo-Darwinism. Concepts like drift and gene duplication, for instance, not only have a long legacy in evolutionary biology, but enjoy an unprecedented level of support today; due in part to the proliferation of experimental evolution and next-generation sequencing techniques.

So if we take the book’s stated aims at face value, the authors seem to be attempting to refute a dead and buried concept in evolutionary biology, and not even doing that in a particularly convincing way.

At this point, I was understandably confused about the theological relevance of this project. Neo-Darwinism is often framed as the antithesis to Intelligent Design, which in turn is popularly taken to be the only way to defend a design argument based on biological phenomena (but see the concluding section of this review). In that particular dialectic context, maybe refuting Neo-Darwinism would serve to aid the case for design. However, if Neo-Darwinism is completely outdated in modern evolutionary biology, as I’ve demonstrated - what would even be the point?

All of this led me to suspect that the authors are trying to do something other than their (and Noble’s) stated aims.

The actual aim of the book is to refute mainstream evolutionary biology

Here’s what I think is happening. When the authors say “Neo-Darwinism”, they don’t actually mean it to entail those four pillars I quoted in the beginning, an outdated paradigm that has no room for non-Darwinian drivers of evolution. Instead, they mean something more akin to “mainstream evolutionary biology”. This should explain why the authors think Neo-Darwinism is as popular in academia as they do; because they’re using that term to refer to the conventional evolutionary paradigm.

This is also in line with how Neo-Darwinism is sometimes defined outside the book. While Neo-Darwinism came to prominence in the first half of the twentieth century, some authors think of it less as a set of concrete ideas and more of the general research program adopted by evolutionary biologists. Such a view would incorporate newer developments in the field, including genetic drift and genome rearrangements. Pigilucci and Muller (2010), for instance, define the “modern synthesis” (taken to be virtually synonymous with Neo-Darwinism by the authors) as the following:

The major tenets of the evolutionary synthesis, then, were that populations contain genetic variation that arises by random (i.e., not adaptively directed) mutation and recombination; that populations evolve by changes in gene frequencies brought about by random genetic drift, gene flow, and especially natural selection… [Evolution: The Extended Synthesis, p. 9]

I think this analysis is correct - the authors are conflating “Neo-Darwinism” with mainstream evolutionary biology, and that’s what leads to confusion.

This also explains why, instead of using the more widely discussed phenomena like genetic drift or gene duplication to respond to the threat of Neo-Darwinism, they’re relying on the ideas of a figure who can be read as being anti-mainstream. Noble certainly has ideas that are controversial - for example, his argument that genes have no privileged causal role in the functioning of an organism. If the goal is to challenge the mainstream, it makes sense why these arguments would be preferable to textbook arguments like drift.

With that re-framing in place, what precisely are the authors trying to achieve by utilizing the arguments of Noble against mainstream biology?

The more specific aim of the book is to refute biological reductionism

Noble’s main arguments aren’t even against evolutionary biology per se, but against a particular reductionist conception of biology. Of course, a re-conceptualization of what biological phenomena are would affect how we think about how such phenomena came to be. In that way, his work does have relevance, albeit indirect, to evolutionary biology.

I submit this is the actual goal of the authors: defending an argument against reductionism. This impression is peppered throughout the work, in excerpts like the following:

There is no mind in Dawkins’ deterministic, fatalistic worldview—only body. Therefore, no gene ‘thinks’—thought is an illusion, as are your feelings, hopes, and human rights—all that exists are genes that have a survival advantage and thus propagate. [p. 23]

This mechanistic reductionism we see in the mind of Dawkins and those like him is nothing new. It is a wish to reduce anything and everything to simple physical processes. [p. 29]

By refuting the particular brand of reductionism championed by Dawkins, the authors hope to secure a victory in favor of something akin to anti-physicalism, where not everything is reducible to matter. If biology is little more than nuts and bolts bumping into each other, the prospects of an evolutionary explanation of biological phenomena look more promising. This is why a non-reductionist view of the world arguably fits better with theism than naturalism, and you have the makings of a design argument.

Dawkins, the thinker in the crosshairs of the book, sometimes promotes a very austere form of reductionism according to which all of biology is reducible to DNA sequences of an organism. Here’s one of his quotes from the debate he had with Noble:

Suppose you put Denis’ genome in a petri dish and keep it going for ten thousand years. Well, it wouldn’t keep going; it would decay, as you rightly say. However, the information could be preserved on paper. You could actually write it down in a book, or you could carve the A, T, C, and G codons in granite and keep it for ten thousand years. Then, in ten thousand years, type it into a sequencing machine, which we already have, and it would recreate an identical twin of Denis Noble. [Quoted in Death of Neo-Darwinism, p. 17]

In the eyes of the authors, Noble’s work provides a strong counter to this type of thinking.

This re-framing of the book’s aim makes more sense to me, but it still strikes me as problematic for at least two reasons.

Again, why not use stronger and more widely accessible arguments?

Firstly, if the goal is to refute the sort of gene-reductionism that Dawkins is promoting above, to my mind one could use far stronger and “textbook” pieces of evidence than those in Noble.

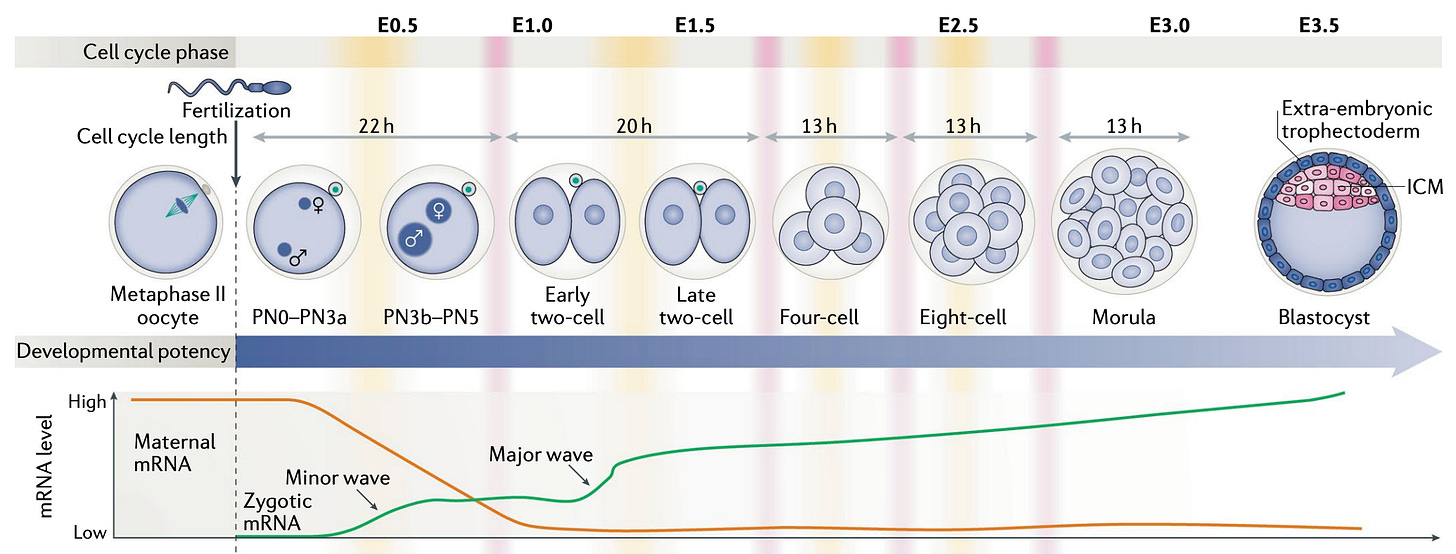

Consider what happens following the fusion of the sperm and the egg. During the earliest phases of animal development, the fate of the new organism isn’t determined by its own genes, but instead the mother’s RNA and proteins found in the egg cell. Depending on the egg cell environment and its RNA/protein profile the fate of the developing organism may vary - meaning, the biological information making up the organism is partially specified by factors other than its genome. This is an extremely well-attested phenomenon - I just looked up “maternal-to-zygotic transition” on the biology paper database PubMed, and found 412 articles, 156 of which were reviews.

This is part of the reason why Jurassic Park will always fail in real life: There’s been talk of bringing back extinct animals (e.g., woolly mammoths or thylacines) from their DNA sequences found in fossils, but such attempts will never be able to re-create the actual animal. Even if we manage to reconstruct the complete genomes of extinct species’ from their fossil remnants, as we learned above, biological information is also imparted by the embryonic environment where development happens. Mammoth and thylacine DNAs might exist, but their egg cells and embryos don’t - so scientists would have to rely on embryos of their living relatives. This might get us close, but without a mammoth egg cell to house the new DNA, some of the biological information that constituted the original animal has been lost forever. Contra Dawkins, DNA sequence alone can’t specify everything there is to an organism.

Indeed, if you listen to the scientists in charge of these projects - they never claim to be able bring back these extinct animals exactly. Andrew Pask, one of the main researchers involved in sequencing the thylacine genome, speaks of bringing back “a de-extincted thylacine-ish thing”.

Is Noble a good response to biological reductionism?

Recall that in order for the book’s argument to be of any use to apologetics, the authors need to demonstrate that any attempt to reduce biological phenomena to purely physical stuff would fail. However, while Noble is associated with biological “holism” (as opposed to reductionism), he’s hardly the sort of reduction-denier one would need him to be for such an argument to succeed. Indeed, it’s true that Dawkins does reduce all biological phenomena to bits of matter - but so does Noble, just to different bits of matter:

We don’t need convincing that, at the molecular level, molecular processes are all there are. But, to reiterate the theme of this book, that does not mean that we are nothing but a bunch of molecules. Structures and processes at a higher level simply are not visible at the molecular level. . . While vitalism no longer finds favour amongst biologists, it is very much alive and well elsewhere in society. I would like to convince some of my readers in this camp that what they may be looking for in seeing life as a whole rather than the sum of its component parts may well be satisfied by the systems biological approach. Life is wonderful enough. We don’t need to endow it with mystery to appreciate that. [The Music of Life, p. 77-78]

In reviewing the debate between proponents of biological reductionism and holism, the chemist Addy Pross summarizes things this way:

[A] moment’s thought reveals that a reductionist philosophy is at the heart of holism as well. The holistic systems approach to understanding the complexity of a biological system continues to reduce the complex system into simpler elements, though placing greater emphasis on the complex nature of the interactions between those elements. In other words the holistic approach merely preaches a more elaborate form of reduction, one that recognizes that causal relations within a system can be more complex than those implied by a simple bottom-up causal chain. [What is Life? p. 53]

Based on his own words and how other experts have read him, therefore, Noble is just as much a reductionist as Dawkins is, except he reduces things to a more complex, variegated assemblage of matter. But no side of the debate claims that biological phenomena, at bottom, is anything more than physical stuff.

Without further development, therefore, I’m not entirely sure whether Noble’s arguments take us away from physicalism or naturalism.

Concluding remarks: steelmanning, and perhaps a better way forward

Thus far I’ve been discussing the shortcomings associated with the book’s project, but I wouldn’t discount it entirely. I think there might be something to the new science of systems biology and seeing organisms as irreducible wholes that sits more comfortably with theism than naturalism. Michael Denton, a prominent proponent of biological design arguments, wrote in defense of the first premise of this argument. More recently, Scott Turner’s Purpose and Desire has made an extended case for organisms possessing intrinsic teleology on similar grounds. This also overlaps with Thomistic notions of souls, defended in modern times by philosophers like Edward Feser and J. P Moreland (see chapters 6 and 7 of The Blackwell Companion to Substance Dualism). The idea of no privileged level of causation in biology, to the extent organisms can only explained as a whole - might have theism or design-relevant consequences that are worth exploring further. I would totally be on board with a project that aims to develop these themes.

There might be a more involved argument the authors are trying to make, one that doesn’t require ruling out biological reductionism. The Intelligent Design proponent Emily Reeves has argued that emergent biological properties - the sort Noble gestures at - cannot be explained by naturalistic evolution, something that calls to mind Michael Behe-esque objections to evolution. It’s hard to comment on the prospects of this argument without further development, and I welcome efforts to to that end.

With that said, I do feel like when defending biological design, maybe it’s worth exploring arguments that have a stronger legacy and are generally more accessible. If it were up to me, I would probably pay more attention to the arguments made by Michael Denton in his Privileged Species book series, which are a collection of fine-tuning arguments made specifically about human survival and flourishing on earth. The theologian Rope Kojonen has likewise defended an argument which claims biological evolution leading to complexity requires fine-tuning.

These arguments don’t go against consensus views among mainstream biologists, are generally easier to understand, and can ride on the coattails of the more familiar cosmological fine-tuning argument. I think these represent more fertile grounds to explore when it comes to defending design in biology.